Notes on Distributed Consensus and Raft

How and why distributed systems like Kafka and Kubernetes remain in-sync across multiple machines thanks to the Raft algorithm.

In Kafka or Kubernetes, if one machine fails, another steps in. No downtime, no data loss.

what’s the magic behind this smooth coordination? The answer is distributed consensus.

The Raft algorithm is used by these systems to agree (consensus) on the same state across multiple machines (distributed).

Why multiple machines?

But first, why do we need multiple machines? Here are some reasons:

1) Scalability

Modern hardware is impressive. You can get:

- hundreds of gigs of RAM

- terabytes and terabytes of disk space

But you can only scale so much vertically.

At some point your load becomes so big that a single machine can’t handle it anymore, and that’s when you need to split the load across multiple machines, aka horizontal scaling.

2) Reliability (Murphy’s Law)

Have you noticed how your lane on the highway always seems suspiciously slower?

Or how the light turns red right before you get to the intersection?

That’s Murphy’s Law: if something can go wrong, it probably will.

And the same applies to computing.

If a piece of hardware can fail… it probably will. So we want a backup ready to take over the moment failure happens.

That’s why we use:

- multiple machines

- multiple availability zones

- multiple regions

Because hardware will fail, and we need backups to keep going.

3) Performance (and latency)

This is related to scalability but slightly different.

Even before a machine is fully overloaded, once it starts reaching its limit, you can still keep going… but performance degrades.

So we split work across multiple machines to keep performance stable.

Also: sometimes performance is about location.

You want machines in certain regions for latency reasons, a classic example is CDNs, which cache content closer to users.

So what is distributed consensus?

Distributed consensus is simply:

all the machines agreeing on the same shared state

But that raises the next big question:

Why do these machines need to share state at all?

Let’s use Kafka as an example.

Kafka example: why shared state matters

Kafka is an event streaming system.

You can have applications that:

- write messages → producers

- read messages → consumers

Kafka is famous for high performance, and one major reason is how it scales:

Topics → partitions → servers

You can think of a Kafka topic like a table or a place where you send messages/events.

Each topic is split into multiple partitions, and each partition is allocated to a different Kafka server.

So Kafka is made of multiple servers, and each one leads (or is responsible for) a subset of partitions.

Example:

If you have 100 servers, you can split your topic into 100 partitions, spread across all 100 servers.

So when messages are sent, the load is distributed across the cluster.

Kafka decouples producers from consumers

This is one of Kafka’s main selling points: producers don’t need to know who is consuming the data, and consumers don’t need to know who produced it.

A practical example:

Imagine an e-commerce business with an “orders” topic.

Orders can come from multiple places:

- your backend

- third-party integrations

- other services

So multiple producers are publishing orders into Kafka.

On the other side, multiple systems consume the same topic:

- marketing app

- fulfillment app

- machine learning app training a recommender system

All these applications interact with the same topic. And because topics can be partitioned, Kafka scales beautifully.

What happens if a server fails?

Here’s the real problem: each server holds partitions.

So if a server fails, ideally those partitions should move or fail over to another server, and we keep processing like nothing happened.

But to do that, the system needs metadata like:

- which partitions live on which server

- where replicas live

- who is leader for each partition

And here’s the key part:

all the servers need to agree on this shared state

That’s why we need distributed consensus.

Kafka replication makes this even more important

Kafka doesn’t just partition, it replicates.

Each partition has:

- a leader broker responsible for it

- plus replicas hosted on other brokers

So when data is written to the leader partition, it’s also replicated to other machines.

If the leader broker fails, another broker that has a replica can take over.

But again, for that to work, Kafka needs cluster-wide agreement about:

- where each partition lives

- who has which replicas

- which broker is leader

This shared metadata is the “state” that must remain consistent.

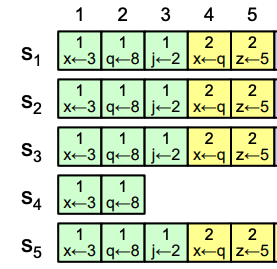

The log: don’t share the whole state — share events

In our small example, the state (partition locations, leaders, replicas) was manageable.

But imagine:

- 10,000 topics

- 100,000 topics

- plus more metadata objects

Do we share the entire state every time something changes?

No.

Instead we rely on a log.

The idea is:

instead of sharing the whole state, share the events that happened to the state

For example:

- assign

x = 3 - assign

y = 1 - and so on

If every machine receives the same events, in the same order, and applies them, they arrive at the same final state.

Same idea for databases:

- create table

- update table

- create another table

- update it

- drop the first table

A sequence of events, applied in order, gets you to the same end state.

This is what Raft does:

Raft tries to ensure all machines have the same log, and once they apply the entries, they reach the same state.

Raft: the understandable successor to Paxos

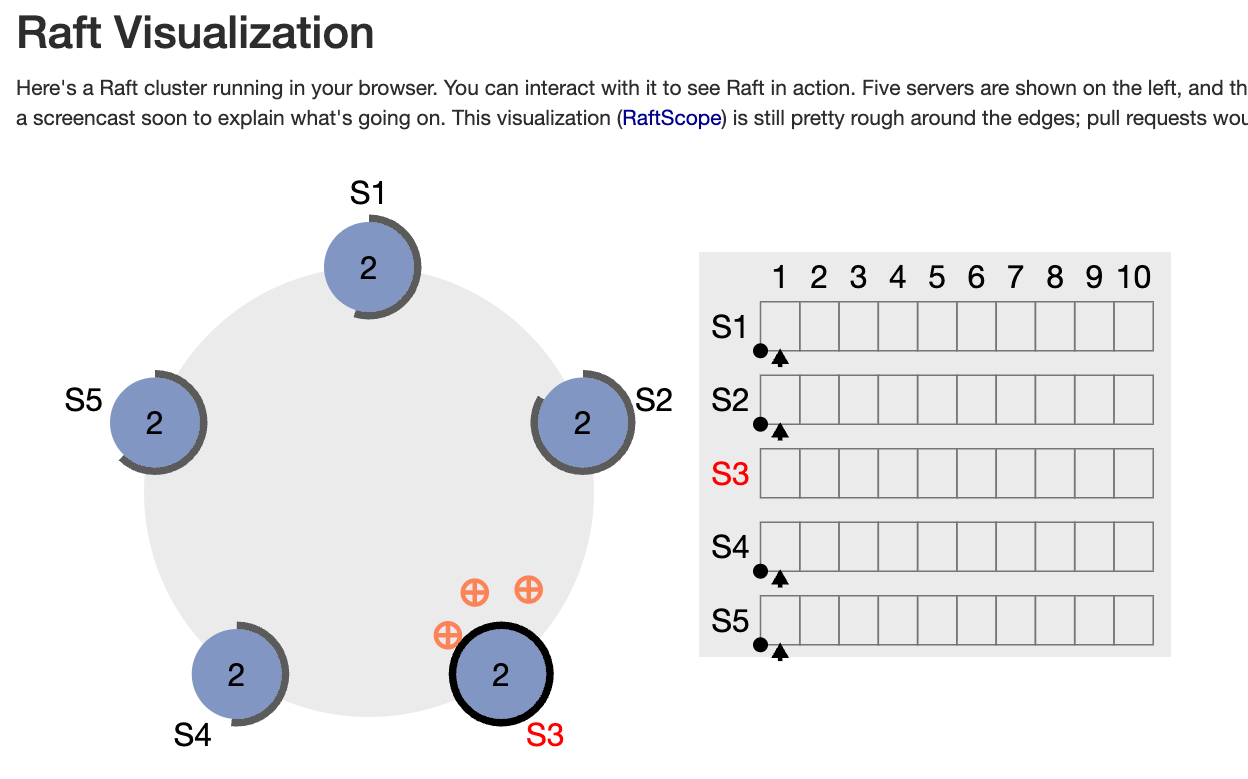

I highly recommend checkout raft.github.io to and playing with the visualization. It also links great resources.

Raft was created as a successor to Paxos, another distributed consensus algorithm.

And the funny thing about Paxos is: it’s extremely complicated.

The designers of Raft explicitly wanted to create something understandable.

So understandability was one of Raft’s design goals.

The core idea: Raft uses a leader

Raft achieves distributed consensus by electing a leader.

In a Raft cluster:

- one node is the leader

- other nodes are followers

If we want to add an entry to the log:

- we send the request to the leader

- the leader replicates it to followers

- once it receives confirmations from a majority, it commits the entry

That majority is called a quorum.

Only committed messages can be acknowledged back to the client.

So:

- if the leader does not get confirmation from a majority

- it cannot commit

- and it cannot safely acknowledge the client request

Leader failure: how Raft elects a new leader

So what happens if the leader goes down?

Raft handles this using timeouts.

Each follower has an election timer. If the follower doesn’t hear from the leader for long enough:

- its timer times out

- it starts a new term

- it becomes a candidate

- it votes for itself

- and sends vote requests to other nodes

If it gets a majority, it becomes the new leader.

Edge case: split vote

What if two nodes time out at the same time and both start elections?

That can create a split vote.

Raft solves this using randomized timeouts, so eventually one node times out first and wins leadership cleanly.

What if we lose quorum?

Let’s say we have 5 nodes.

Majority is 3. (Leader also counts itself.)

If enough nodes fail, and we no longer have a majority, then:

- requests may still be appended to the log

- but they won’t be committed (because we don’t have quorum)

In demos, this shows up like dotted lines: the entry exists locally, but it’s not committed.

Once a missing node comes back:

- it discovers who the current leader is

- fetches missing log entries

- catches up

- acknowledges the entry

- quorum is restored and the dotted entry becomes committed

A quick precision: Kafka and Kubernetes usage

One important detail:

Kafka

Kafka uses a modified version of Raft called KRaft.

Instead of the leader pushing updates, followers pull updates, so it’s more of a pull model.

But the principles remain the same.

Kubernetes

Kubernetes doesn’t implement Raft directly.

It relies on etcd, a distributed reliable key-value store.

etcd stays consistent thanks to the Raft protocol.

Conclusion

So that’s distributed consensus and Raft:

- we use multiple machines for scalability, reliability, and performance

- those machines must agree on shared state

- instead of sharing huge state snapshots, we share a log of events

- Raft keeps logs consistent using a leader, replication, quorum, and elections