Exploring Terminals, TTYs, and PTYs

This post takes a look at terminals, TTYs, and PTYs. We'll look at terminal emulators display text and styles. Along the way, you'll see escape codes, line discipline, signals, and a simple Python example with Pyte to show what's happening behind the scenes.

In case you’re curious about how coding agents work, check out this post where I explore an open-source agent internals.

Intro

Terminals, PTYs, and TTYs feel both familiar and elusive. While exploring TUIs recently, I realized my understanding of terminals needed a refresher. In this post, I’ll share an overview with examples and commands to help clarify these concepts.

Running commands is powerful. It’s often more convenient than using a GUI and enables automation and scripting. A classic use of the terminal goes like this: a terminal program is launched, which starts a shell (like bash), allowing us to run commands. Each time we enter a command, the shell forks a new child process, runs the command, and passes it arguments.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

# Step 1: Create the Python script using HEREDOC

cat <<'EOF' > myscript.py

import sys

print("Script name:", sys.argv[0])

print("Arguments:", sys.argv[1:])

EOF

# Step 2: Run the script with arguments

python3 myscript.py first_arg second_arg blabla

# Output:

# Script name: myscript.py

# Arguments: ['first_arg', 'second_arg', 'blabla']

The terminal is the program that provides the text window (iTerm2, xterm, etc.), while the shell is the program that reads and executes our commands by forking child processes. There are different shells (bash, zsh, sh, etc.). The two are related but quite different. Running echo $SHELL tells us which shell we’re currently using.

The Basics

Before monitors and GUIs, people interacted with computers through terminals. These were large boxes like this one:

They displayed only text, and earlier versions didn’t even support color or fonts. In Unix-like systems, everything is a file, and terminals are no different: they’re character devices that receive data from a process, display it, and send data from the keyboard back to the process. Echo mode is when typed characters are also sent back to the display so you can see what you’re typing.

tty, which stands for teletypewriter, originally referred to physical terminals. Today, it refers to virtual ones.

Virtual Console TTYs are software emulations of terminals provided by the kernel. They reside in

/dev/ttyN. In Linux, you can access Virtual Console 1 usingCtrl+Alt+F1. These consoles are built into the kernel and are often used for recovery if the GUI fails or to operate a headless (non-GUI) server.Terminal emulators such as iTerm on macOS or GNOME Terminal on Linux, are applications that run within the graphical user interface (GUI) of the operating system (e.g., X11 or Wayland on Linux, Aqua on macOS, or the Windows UI). These terminals rely on pseudo terminals (PTYs) to emulate terminal behavior. (More on that later.)

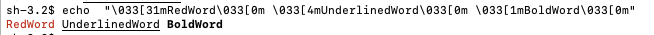

Terminals can do more than just show plain text: they can display color and handle special operations like clearing the screen or moving the cursor:

1

echo "\e[31mRedWord\e[0m \e[4mUnderlinedWord\e[0m \e[1mBoldWord\e[0m"

These are the ANSI escape code, basically a way to indicate formatting tino the terminal. Much like HTML/CSS are used in the browser.

Here:

\e[31msets red foreground\e[4msets underline\e[1msets bold\e[0mresets formatting

\e is the escape character (ESC, ASCII 27). It can also be written in hexadecimal as 0x1B (16 + 11 = 27) or in octal as 033 (3 × 8 + 3 = 27).

The following commands produce the same result:

1

2

3

echo "\0x1B[31mRedWord\0x1B[0m \0x1B[4mUnderlinedWord\0x1B[0m \0x1B[1mBoldWord\0x1B[0m"

echo "\033[31mRedWord\033[0m \033[4mUnderlinedWord\033[0m \033[1mBoldWord\033[0m"

Some other escape codes:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# clear screen

echo "\033[2J"

# move cursor up 3 lines

echo "\033[3A"

# move cursor down 4 lines

echo "\033[4B"

# RGB colors

echo "\033[38;2;<r>;<g>;<b>m"

There’s even a bell code (\007):

1

echo "bell in 5 seconds...\n"; sleep 5; echo "\007"

Fun!

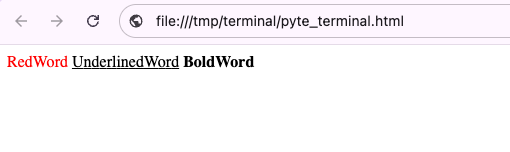

An HTML Terminal

What happens under the hood? A terminal emulator keeps an internal representation of each position on the screen, along with the cursor and other state. When we send an escape sequence to, say, set the color to red and underline text, the emulator updates that internal representation accordingly and then renders what we asked for.

Pyte is a neat terminal emulator written in Python. It takes in a stream of bytes like a real terminal would, and updates an in-memory representation of the screen. For example, if we feed it "Hello World", Pyte places those characters into cells of a 2D screen buffer it maintains in memory. If we include escape codes for color, bold, or underline, Pyte marks the corresponding cells with those styles. It also keeps track of the cursor position and moves it as escape sequences dictate.

With Pyte, we can take ANSI input, inspect the cell states, and render them however we like. A serious terminal emulator would draw the result on screen using the OS’s graphics API, but in this simple example we’ll render it as HTML instead:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

from pyte import Screen, Stream

# Setup

screen = Screen(40, 20) # 40x20 terminal screen

stream = Stream(screen)

# Feed some ANSI

stream.feed("\033[31mRedWord\033[0m \033[4mUnderlinedWord\033[0m \033[1mBoldWord\033[0m")

# Convert screen buffer to HTML

def screen_to_html(screen):

html_lines = []

for y in range(screen.lines):

row = []

for x in range(screen.columns):

cell = screen.buffer[y][x]

if cell.data == " ":

# Non-breaking space for empty cells

row.append(" ")

else:

styles = []

if cell.fg:

styles.append(f"color:{cell.fg}")

if cell.bg:

styles.append(f"background:{cell.bg}")

if cell.bold:

styles.append("font-weight:bold")

if cell.italics:

styles.append("font-style:italic")

if cell.underscore:

styles.append("text-decoration:underline")

style = ";".join(styles)

row.append(f"<span style='{style}'>{cell.data}</span>")

html_lines.append("".join(row))

return "<br/>\n".join(html_lines)

html = screen_to_html(screen)

with open("pyte_terminal.html","w") as f:

f.write(html)

print(html)

# <span style='color:red;background:default'>R</span><span style='color:red;background:default'>e</span><span style='color:red;background:default'>d</span><span style='color:red;background:default'>W</span><span style='color:red;background:default'>o</span><span style='color:red;background:default'>r</span><span style='color:red;background:default'>d</span> <span style='color:default;background:default;text-decoration:underline'>U</span><span style='color:default;background:default;text-decoration:underline'>n</span><span style='color:default;background:default;text-decoration:underline'>d</span><span style='color:default;background:default;text-decoration:underline'>e</span><span style='color:default;background:default;text-decoration:underline'>r</span><span style='color:default;background:default;text-decoration:underline'>l</span><span style='color:default;background:default;text-decoration:underline'>i</span><span style='color:default;background:default;text-decoration:underline'>n</span><span style='color:default;background:default;text-decoration:underline'>e</span><span style='color:default;background:default;text-decoration:underline'>d</span><span style='color:default;background:default;text-decoration:underline'>W</span><span style='color:default;background:default;text-decoration:underline'>o</span><span style='color:default;background:default;text-decoration:underline'>r</span><span style='color:default;background:default;text-decoration:underline'>d</span> <span style='color:default;background:default;font-weight:bold'>B</span><span style='color:default;background:default;font-weight:bold'>o</span><span style='color:default;background:default;font-weight:bold'>l</span><span style='color:default;background:default;font-weight:bold'>d</span><span style='color:default;background:default;font-weight:bold'>W</span><span style='color:default;background:default;font-weight:bold'>o</span><span style='color:default;background:default;font-weight:bold'>r</span><span style='color:default;background:default;font-weight:bold'>d</span> <br/>\n <br/>.....

Nothing too fancy. We feed the same sequence we used above (

Nothing too fancy. We feed the same sequence we used above (\033[31mRedWord\033[0m \033[4mUnderlinedWord\033[0m \033[1mBoldWord\033[0m) to Pyte. The library updates its internal representation of the screen based on that input. Each cell has a data field for the actual character, along with other fields describing its style: foreground color, background color, italic, underline, bold, etc. We then iterate over those cells, adjust the HTML styles accordingly, and display the result. That’s it.

This is, of course, extremely inefficient, but it gives a concrete sense of how an emulator works.

TTY

When we run a program from the terminal, it has a controlling terminal, usually /dev/tty. Programs that expect a terminal will check for it and fail if they don’t find one. A TTY also provides signals (SIGINT, SIGTSTP, etc.) and job control (more on that later). SIGHUP is a signal sent when the terminal is closed. By default, processes terminate when they receive SIGHUP. It can also be used as a signal for the process to reload its configuration after a change (e.g. [Prometheus](https://prometheus.io/docs/prometheus/latest/configuration/

A program without a TTY (a controlling terminal) is typically run without explicit invocation from the terminal: for example, through a cron job, systemd, at, etc.

1

2

3

4

ps -o pid,tty,comm

PID TTY COMM

57040 ttys002 /bin/zsh

57041 ttys004 /bin/zsh

ttys002 and ttys004 are pseudo-terminals created by my terminal emulator.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

# run

sleep 123456

# other terminal window

ps -ef | grep sleep

502 87626 84877 0 12:35PM ttys049 0:00.00 sleep 123456

# closing the first window kills the 'sleep' process because of the SIGHUP signal

# now, let's run the sleep command with nohup which blocks SIGHUP

nohup sleep 123456 &

# close terminal and open another one

ps -ef | grep sleep

502 87810 1 0 12:36PM ?? 0:00.01 sleep 123456

# Notice the `??`, which indicates the process doesn't have a controlling terminal

PTY

One essential concept when working with the terminal is PTY. When a terminal emulator (xterm, Terminal, etc.) interacts with a child process, it does so through a PTY.

A PTY (pseudo-terminal) is simply two virtual character devices/files: a parent (master) and a child (slave). For the process connected to the child, it behaves exactly as if it were connected to a real terminal. For the process connected to the parent, anything written to the parent is passed to the child as input, and anything written by the child can be read from the parent. A nice bidirectional communication channel.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

import os

import pty

import select

def parent_child_communication():

pid, parent_fd = pty.fork()

if pid == 0: # pid is 0 only for the child, this is how linux's `fork()` behaves

os.write(1, b"Hello from child (child process)!\n")

read_back = os.read(0, 1024)

response = f"Got it. I, the child, received: {read_back.decode()}\n".encode()

os.write(1, response)

os._exit(0)

else:

print("Parent: Reading from parent...")

# select is used le to wait for input to become available on parent_fd with a timeout of 1 second.

rlist, _, _ = select.select([parent_fd], [], [], 1)

if rlist:

output = os.read(parent_fd, 1024)

print("Parent: Received ->", output.decode())

os.write(parent_fd, b"Hello from parent (parent process)!!\n")

rlist, _, _ = select.select([parent_fd], [], [], 1)

if rlist:

output = os.read(parent_fd, 1024)

print("Parent: Received back 1 ->", output.decode())

output = os.read(parent_fd, 1024)

print("Parent: Received back 2 ->", output.decode())

os.close(parent_fd)

parent_child_communication()

# Output:

# Parent: Reading from parent...

# Parent: Received -> Hello from child (child process)!

# Parent: Received back 1 -> Hello from parent (parent process)!!

# Parent: Received back 2 -> Got it. I, the child, received: Hello from parent (parent process)!!

Notice we have two received back: 1 and 2. Why? Well, because of echo!! The parent gets its input back first, then the child’s response.

Why do we need PTYs?

Why? Why do we need this? Why can’t a parent just fork a process and read from stdin and stdout? Maybe it’s because people are fond of simpler times and want to honor them by keeping the old ways alive. Not really.

Many programs (bash, vim, ssh, etc.) expect a terminal. Unix’s TTY layer provides functionalities these programs rely on, notably line discipline.

1

2

3

# vim expects a tty input

vim </dev/null

Vim: Warning: Input is not from a terminal

Line discipline handles things like:

Backspace and delete: They are just characters. The fact that they actually erase a character and move the cursor is handled by line discipline.

Canonical (cooked) vs. raw mode: In cooked mode, input is line-buffered. The program (usually the shell) only sees what you type after pressing Enter. This behavior is provided by the kernel’s TTY. Some programs such as TUIs or text editors like Vim switch the terminal to raw mode because they want finer control.

- Example:

stty -icanon; catdisables canonical mode (switches to raw). Backspace is displayed literally for instance, as^?.

- Example:

Echoing: Seeing what you type as you type is managed by the kernel’s TTY layer. Being able to disable echo is also important. When you type a password in the terminal and nothing shows up, that’s because echoing was disabled.

- Example:

stty -echo; catdisables echoing. This is what happens for password fields (still in cooked mode).

- Example:

Signals: Processes in Linux can use signals to communicate. PTYs let you send signals via keyboard input. For example:

Ctrl-CgeneratesSIGINTand stops the process immediately.Ctrl-\generatesSIGQUITand stops the process, also creating a core dump (a snapshot of the process’s memory).Ctrl-ZgeneratesSUSPand suspends the process, letting you resume it later (fg/bg).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

# start vim then press ctrl+Z to suspend

➜ $ vim file.txt

[1] + 77825 suspended vim file.txt

# list jobs

➜ $ jobs

[1] + suspended vim file.txt

# resume vim in foreground using fg

➜ $ fg %1

[1] + 77825 continued vim file.txt

Flow control: When a process writing to STDOUT sends data faster than you can read (flooding the screen), you can pause and resume output:

Ctrl-Spauses output.Ctrl-Qresumes it. Example:

1

for ((i=1; i<=100000000000000; i++)); do echo $i; done

Pressing

Ctrl-Spauses output, pressingCtrl-Qresumes it. This is different fromCtrl-C(kills the process) orCtrl-Z(suspends it). With flow control, the process isn’t suspended, it’s just blocked on thewriteto stdout.Window size and resize events: These are provided via PTY so that TUIs/editors can be notified when the terminal window is resized.

Example:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

# Start vi vi /tmp/test.txt # In another terminal, find its TTY $ ps 70035 ttys040 0:00.04 vi /tmp/test.txt # Trigger a resize event, making vi think the terminal has only 10 rows $ stty -f /dev/ttys040 rows 10

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

# run this to trap the resize event then try resizing the terminal window # The `trap` command in bash (and other shells) lets you catch signals and run code when they occur. trap 'echo "Resized to $(stty size)"' SIGWINCH ➜ ~ Resized to 48 158 ➜ ~ Resized to 48 157 ➜ ~ Resized to 48 156 ➜ ~ Resized to 48 155 ➜ ~ Resized to 48 154 ➜ ~ Resized to 48 153 ➜ ~ Resized to 48 154 ➜ ~ Resized to 48 155 ➜ ~ Resized to 48 156 ➜ ~ Resized to 48 157

Running stty -a shows the current terminal options:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

$ stty -a

speed 9600 baud; 43 rows; 152 columns;

...

cchars: discard = ^O; dsusp = ^Y; eof = ^D; eol = <undef>;

eol2 = <undef>; erase = ^?; intr = ^C; kill = ^U; lnext = ^V;

min = 1; quit = ^\; reprint = ^R; start = ^Q; status = ^T;

stop = ^S; susp = ^Z; time = 0; werase = ^W;

Here, the terminal size is 43 lines by 152 columns. We can also see the list of control characters, familiar ones like ^C, ^S, ^Q, ^Z. Two other famous ones:

werase(^W) deletes the previous wordkill(^U) erases the entire input line

We can even change them. For instance:

1

stty intr ^J

This makes Ctrl-J act like Ctrl-C (send SIGINT to stop the process).

SSH

With SSH, we want to connect to a remote machine. On our local machine, we have an SSH client program, and on the remote machine, an SSH server is listening. Through this connection, we effectively simulate access to a terminal on the remote machine.

The SSH server spawns a PTY (pseudo-terminal) to connect the shell. Why not just use plain stdin/stdout? For the same reasons mentioned earlier: line discipline, interrupts, and window size handling. For example, when we resize our terminal window, a resize event is sent through the SSH TCP channel and updates the remote PTY. Programs that need to know the window size are then updated via a SIGWINCH signal.

Terminal-based applications (like vim, htop, less, etc.) can handle SIGWINCH and redraw themselves to fit the new dimensions.

Conclusion

There are a ton of things left to cover, but let’s stop here.

Terminals are definitely a lot of fun! I had some scattered knowledge about these topics, but reading up on them and writing about it helped crystallize the concepts a little better. It’s really a miracle that modern computer systems work the way they do. There are a gazillion pieces under the hood, and whenever you peek inside, a fascinating world lies beneath!

Get in touch on Twitter/X at @moncef_abboud.